Table of Contents

These are, then, problems ripe for an underground push. Despite Beijing’s restricted handle of the printed term and its dissemination, a new and diffuse network of underground printers — small-tech, economical, remarkably flexible, and extremely hard to law enforcement — springs up. Equipped with nothing at all more than Chinese typewriters, mimeograph devices, and stencil duplicators, underground publishers mass-develop an untold amount of products for a huge and varied readership.

I used the better element of 15 decades collecting these at the time unlawful journals, newspapers, and books — as well as gear utilised to make them, and I have given that donated the trove — the world’s biggest — to Stanford University.

Radical equipment

China’s underground push printed publications, newspapers, and even e-book-duration publications. Dayinben — “typed and mimeographed editions” — represent a unique species of Chinese guide, standing along with woodblock prints, lithographic publications, and letterpress books.

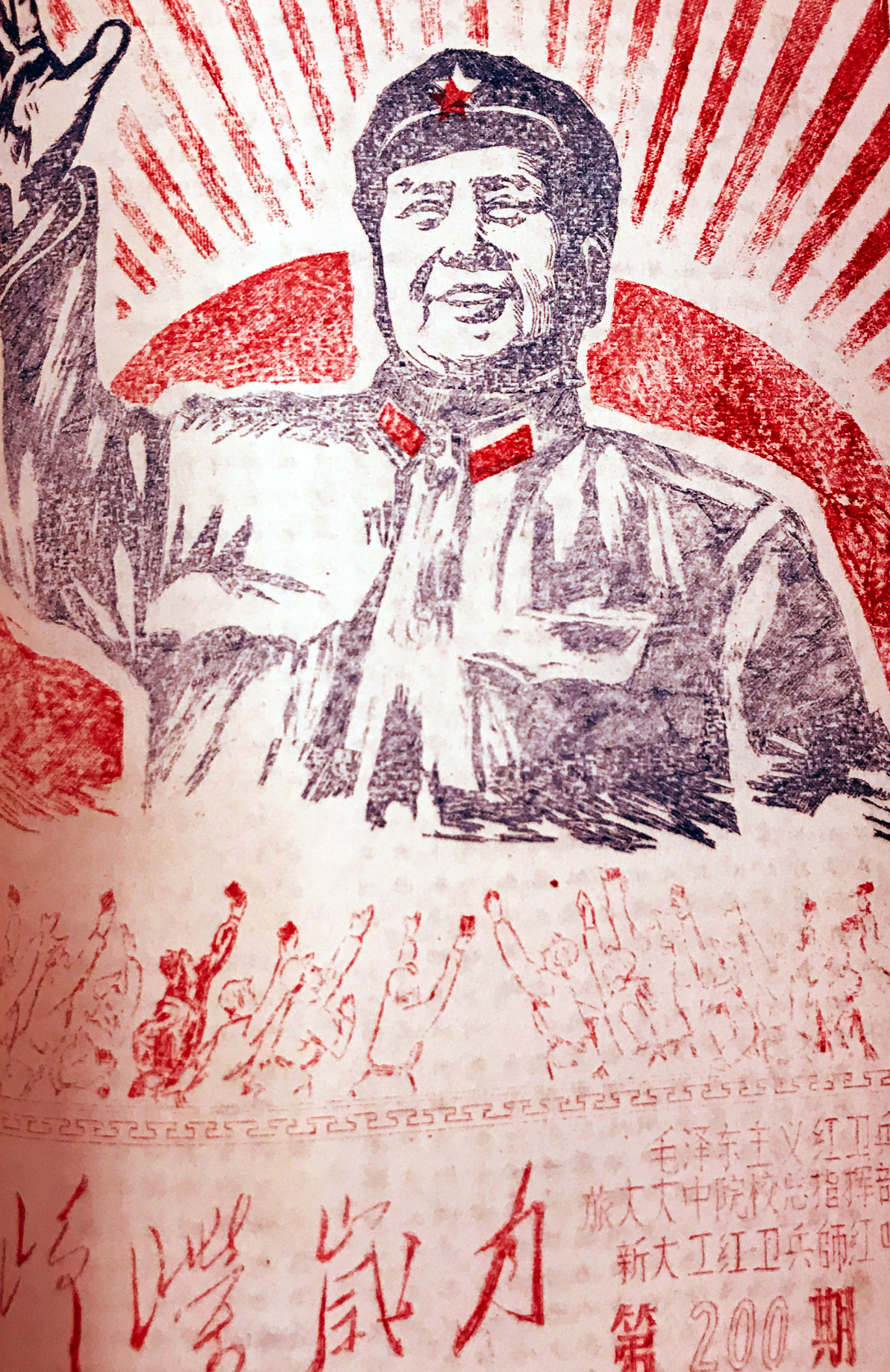

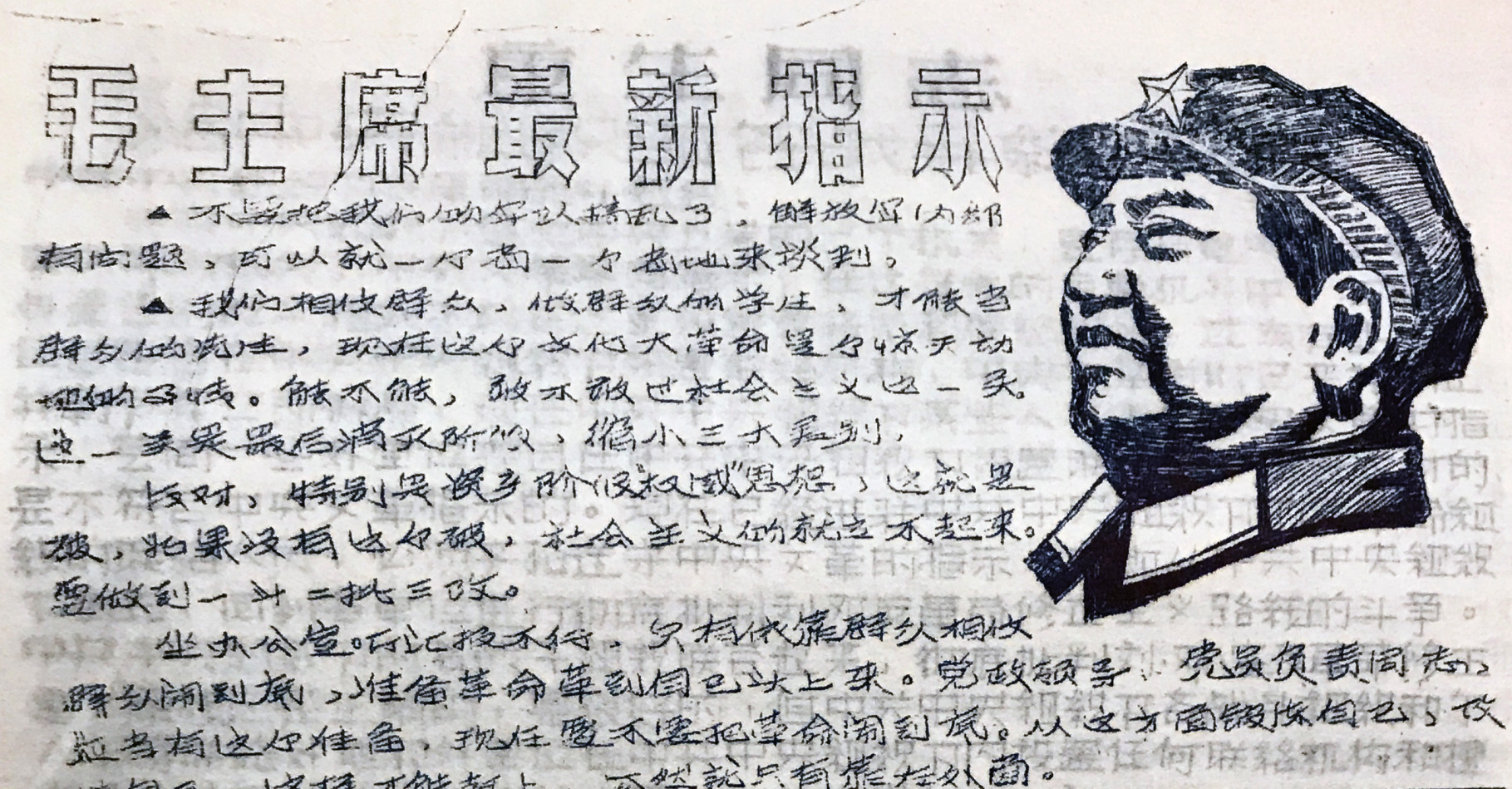

For people who did not have obtain to a Chinese typewriter, the mimeograph produced it possible to make fully hand-drawn books, magazines, and newspapers. A e-newsletter that includes a stencil drawing of Mao is a very good case in point of a publication drawn solely by hand and reproduced lots of situations around for distribution.

All instructed, China’s underground zines had been so many that the term for them survived into the laptop or computer age: No more time “typed and mimeographed,” dayin now signifies “to print out,” as with a laser printer. In the previous days, in spite of becoming minimal-tech, underground push print runs could be as significant as 1,000 copies — the standard first-operate printing of most university presses these days.

New music, poetry, literature, and science

Underground did not necessarily imply anti-Occasion or anti-condition. In 1 typed-and-mimeographed zine from 1968, a self-discovered Pink Guard reproduced Mao’s poetry, releasing the version in time for International Workers’ Working day. In an even extra profound act of devotion, customers of the “Yunnan University Mao Zedong-ism Artillery Regiment Overseas Language Division Propaganda Group” transcribed Mao’s speeches from 1957 and 1958. At a lot more than 280,000 people, with site following site dense with text, this perform would have taken between 100 and 200 hrs — or four to 8 full days — to form.

The underground press gave an outlet to other poets, writers, and creators, foremost to a flourishing of self-expression. This involved songbooks and musical scores. Songs notation is notoriously tricky to print utilizing movable sort systems, supplied the quite a few various varieties of notes and symbols, but it lent alone to the underground procedures. A single could kind lyrics working with a Chinese typewriter and use a combination of a difficult-tipped creating instrument and straightedges to make the tunes staves, notes, and musical symbols (legato, fortissimo, etcetera.).

The very low-expense underground methods ended up also a boon to scientists and engineers who may not or else have uncovered a publisher ready to justify the price of printing such hyperspecialized titles as “Discussion on Transverse Cracks in Strengthened Concrete in Single-Tale Industrial Workshops” (c. 1963), “Collection of Technical Requirements for Paper Business Products” (1972), and “Fluid Mechanics and Fluid Machinery” (1975). This kind of niche publishing continued into the publish-Mao era, which started in 1976.

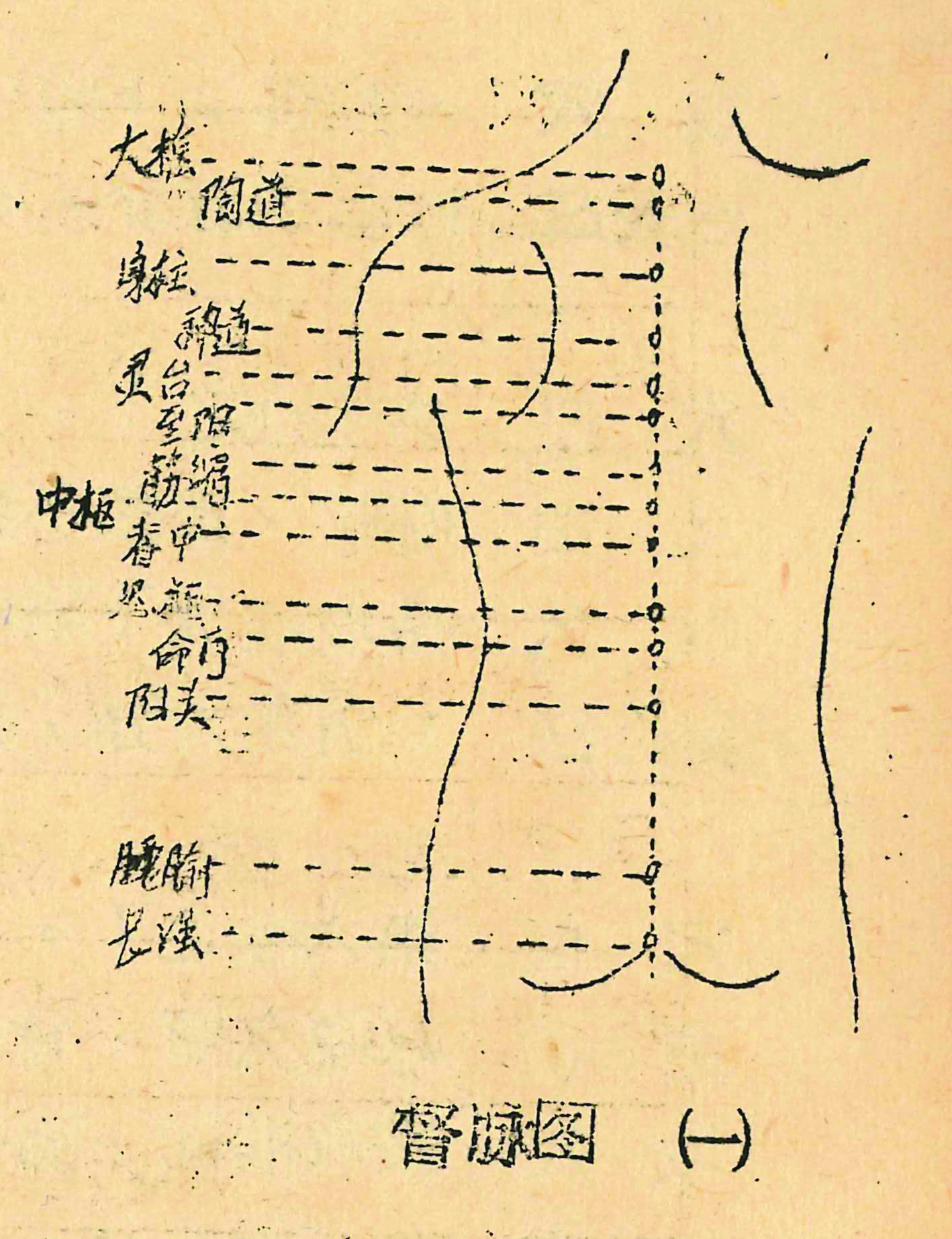

In equivalent style, textbook and handbook authors turned to the underground push to make their will work on such subject areas as standard Chinese drugs. Other than the very low charge, the underground press also appealed simply because of its flexibility. An creator could quickly merge text, tables, and complex diagrams on the exact same web site. Undertaking so applying regular tactics was both of those high-priced and technically challenging. In this regard, China’s underground publishing community was central to the dissemination of know-how about science, know-how, engineering, medication, and the arts all through the Mao era and beyond.

The Party and the underground press: an uneasy romance

The Communist point out alone turned to underground presses when the requires of mass mobilization campaigns outpaced Chinese clerks’ and typists’ capability to develop the financial reports and tracts utilized in work-unit “study sessions” across the region. So weighty was the stress on Chinese typists that some get the job done models resorted to outsourcing employment to unofficial “type-and-copy shops” — dazi tengxieshe.

But there was pressure. The Chinese Communists tacitly recognized the existence of the underground press even as they knew the same retailers they patronized have been generating subversive components. So the Chinese Communist point out made specific forensic strategies to detect which stencil equipment and mimeograph devices ended up applied to generate which documents. By analyzing the one of a kind crosshatch styles still left in excess of from the stencil-making method — in impact, a distinctive “fingerprint” — point out authorities would try out to detect an unlawful publication’s origins. Akin to “typewriter forensics” in the Soviet Union and the Japanese bloc, where by analysts analyzed slight variants in the output of various typewriters, this strategy gave Chinese Communist authorities a limited ability to identify authors and deliver them to heel.

The zines that emerged throughout this period of time — exclusive, colorful, painstakingly produced — have been born of necessity and developed at excellent particular risk, and they remind us of the ability of individual expression. And the tradition continues: In today’s Hong Kong, epicenter of so significantly upheaval, riot, and electronic surveillance, younger people today have revived the artwork of the zine, respiratory new existence into an previous means of subversion.

Thomas S. Mullaney is professor of Chinese record at Stanford University and author of “The Chinese Typewriter.” Comply with him on Twitter @tsmullaney and on TikTok @modernchinesehistory.